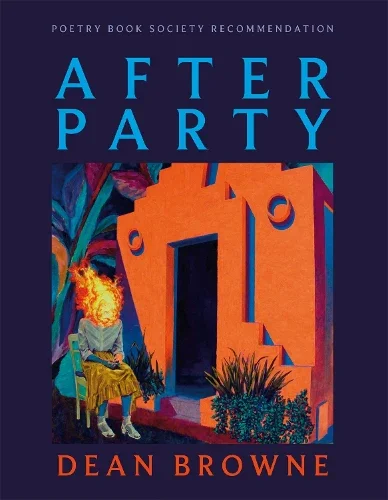

October 22, 2025: launch speech for ‘After Party’

I had been looking forward to Dean Browne’s debut poetry collection since 2017, when I first met him and began reading his work. In the eight years since, I had taken photos of his poems as they appeared in magazines, and had texted them to friends. So it felt really special to be in Books Upstairs, holding this book in my hands, and sharing my enthusiasm for Dean’s extraordinary work with people whose phone numbers I didn’t yet have.

*

Dean Browne is a poet who shoots for the stars, and on more than occasion in this debut collection, the moon. Yet he’s also a poet who – if you can pardon my use of a well-worn expression – has his feet on the ground. Here’s the speaker of one poem describing their favourite shoes of all time:

More akin to ousted nestlings now

than brogues, the laceless caramel suede

withered scrotal. Once, daylight was kinder,

bouncing back off the polished toecaps.

Bouncing is such an operative word for these poems, where lines and images ping, glance, and ricochet, as in the pinball machine evoked so tenderly in a poem here for the late Matthew Sweeney. A wizard is how Sweeney is described at the poem’s close – as in pinball wizard, of course, but the poem invites us, I think, to also consider poets as potential figures of wisdom, capable of enacting supernatural transformations in the world. In this sense, ‘wizard’ is a fitting epitaph for Sweeney – and wizardry is an apt description for Dean’s own achievements in this collection.

Because there’s certainly something magical about this book. Something spellbinding. Reading the collection is like attending a magic show – and watching a rabbit hop up onto the stage and pull a magician out of a hat. Only for you to realise the hat isn’t a hat: it’s time-space, and we’re all floating through it.

I don’t know how Dean does it, but in feats of miraculous compression, he can – with the flourish of a single word – turn a poem, an image, a feeling, inside-out. Often, but not always, it’s in the poem’s final lines. Indeed, his endings are consistently astonishing, and I found myself writing down my reactions when I finished each one. I’ll share with you now a handful of them:

I could read this poem my entire life.

So, so, so, so, so good.

This one seems to come from nowhere – and has left me shook.

These poems are like accordions

I ADORE THESE POEMS!

Why do I adore them? My explanations are many, and will likely evolve with each reading. But one crucial reason is that these poems feel to me like charms that have been conjured to ward off A Dulling Of One’s Senses. Encountering these poems has wiped the windscreen of my perception clear; the fog has lifted, and it’s as if I can see my life again. The other night, after re-reading this collection ahead of this evening, I was brushing my teeth with the bathroom window open. Looking at the stone window-ledge outside I noticed lichen, the colour of Lucozade, creeping over the stone, and the image suddenly seemed so vivid. I must have absent-mindedly gazed at that lichen every night for two years without ever really taking it in, but inhabiting Dean’s poems took me out of my head – and brought the world back to me, allowing me to see my home environment anew.

The experience brought to mind the Russian critic Viktor Shklovsky who in his 1917 essay, ‘Art As Technique’ defined ‘defamiliarisation’ as the act of making the ordinary strange. In his case for the necessity of art, he explains how our habits of the everyday can dull our feeling for life. ‘Habitualization,’ Shklovsky writes, 'devours work, clothes, furniture […] and the fear of war’.

‘Art,’ he writes:

exists that one may recover the sensation of life; it exists to make one feel things, to make the stone stony […] The technique of art is to make objects ‘unfamiliar,’ to make forms difficult, to increase the difficulty and length of perception because the process of perception is an aesthetic end in itself and must be prolonged.

And so, in After Party:

—a pig is described as ‘a pink beanbag full of bones’.

—In one poem, we are invited, perhaps, to transform or dream ourselves into the body of moth, ‘just to feel the walls. the ceiling against your heels’.

—In another poem, garlic cloves are tossed into the pan ‘like a couple of dice’.

—In another, ‘you inhale fathers of tobacco-smoke from suede’.

—while in a poem titled ‘The Leg’, a leg takes off on a train journey, and the poet asks: ‘What did the leg see out the window?’

Art, Shklovsky, argues, salvages our lives from the automatic and habitual not-seeing of our everyday experience. Dean’s poems – themselves works of art – do this for me, and to me. They put a frame around my everyday life and say: Wake up, Tom, pay attention. But no, that’s too hectoring – the poems are far more inviting than that. ‘In Party After The The’, the speaker celebrates a basil plant picked up for ‘two euros in the supermarket’s godless fluorescence’:

‘Why not sniff’, the speaker urges. ‘Be late to the appointment sniffing.’

The basil plant feels to me now quintessentially Brownean – something uprooted from one place, transplanted to another, and ultimately changing itself and its environs. It also, in this poem, speaks to the quiet pleasures that can be savoured in the domestic. In more than one poem, Dean recounts – and honours – the act of preparing a meal for someone else; the certain peace found in the intimacy and harmony of a shared existence played out in the close quarters of the ‘sad inadequate apartments we rented successively’.

I can see so vividly the kitchens in these poems: the spice racks, the basil plants on the window-ledge. I can hear the dicing of the garlic, the sizzle of the pan, as a Joni Mitchell song plays through the Bluetooth. And I can feel the warmth in the room as a bottle of red wine is opened, and the figures in these poems try to make for themselves and their partners a dinner, a home, a life.

In this way, then, the ordinary glows.

Read individually, each of these poems are exquisite explorations of that Paul Klee description of drawing as ‘taking a line out for a walk’. Except when Dean Brown takes a line out for a walk, we often end up ‘skiing off’, as he puts it in one poem, or floating over roofs, like a figure in a Chagall painting; or holding onto one another, as we ‘gingerly’ negotiate a road suddenly covered in snow. But it was only when I read these poems successively that I began to appreciate an extraordinary trait of Dean’s work – the way in which each poem seems to dramatise its own composition and existence. Again, I can’t tell you how he’s achieved this, but there’s nothing wanky or overly-meta in his approach. Rather, I think, Dean is a poet who has melded form and content with such seamless cohesion that the poems’s concerns appear inseparable from their forms.

In this way, it’s as if each poem could be justifiably compared with the very actions it describes. And so the poem is a child looking at the moon through a telescope; the poem is Buster Keaton ‘shunting railroad ties’ knowing it could all go wrong; or the poem is a spider, waiting to ‘sly down’ and bite your neck.

After Party is a collection of poems, yes, but also a collection of strikingly alive definitions of poetry what can be. And yet, for all the poems’s clues about how to unlock their doors, for all their invitations to look at life afresh, these are poems that do allow certain mysteries to remain mysteries; in fact, they are poems whose mysteries deepen with each re-reading.

’It’s not my place to say’, one poem ends – which got me thinking about the poet’s place, and what is theirs to say. As I wondered about this and kept reading, I found – as often in my experience of this collection – that Dean Browne had already got there before me, offering up in the final lines of ‘Butternut Squash’ another irresistible definition of a poem, or a poet, or a life lived attentively:

I am cubing the squash

as precisely as I can, as if

somewhere it’s not too late

to describe these things. To try.