WHITTLING UP

‘In my work as an editor, and later as a mentor at The Stinging Fly, ‘whittling up’ was something I encouraged authors to do, as I worked with them through multiple drafts. I’d ask an author to push through – and move towards the heat. There’s something here, I’d say, pointing towards a description, a word choice, or a particular passage. Go towards it, see what’s there. You can always draw back afterwards…’

After graduating in 2009, I interned at the Lilliput Press, where I read submissions and proofed forthcoming titles. The following year, I worked for writing4all.ie, a writing forum run by a self-publishing house, where I again read submissions and was a filter judge for their annual story competition. (Danielle McLaughlin and Alan McMonagle were the winners in 2009 and 2010). Around this time, I also began reading the fiction that was being published in Irish literary magazines. In the main, I found that the vast majority of the stories I encountered were lacking in some essential ways that I couldn’t quite articulate. I realise now that my data sample was far from exhaustive and skewed towards the unpublished – and I know that every author’s theory of reading contains a strong dose of projection – but over the next few years I began to suspect that a dampened down, almost-depressed style was constraining the aesthetic, intellectual and emotional range of fiction being attempted and published by emerging writers in Ireland. There was a sameness and deadness to the manner of telling: a lack of genuine engagement with modernity; an absence of humour; and a certain fatalistic solemnity that pre-determined the story’s imaginative possibilities. I felt that many of the stories I encountered bore a stronger resemblance to other short stories, rather than to life itself – when life was the thing I was really after.

If this is true – and it’s a big if – then the emerging authors were likely emulating and imitating what they saw being published. They often do – and I certainly was. At that time, a lot of writers, myself included, had come to believe that short stories should be realist, spare, quiet, restrained. Each of these qualities are wonderful in their own way, but the conventions had hardened to the point that it was difficult to remember that realism itself was a convention, and that everyone’s realism is different to each other’s. “Show, don’t tell” was the mantra, and at the story’s close I might allow myself a lyrical “And in that moment…” denouement, which symbolically gestured at some buried and mostly unspoken meaning. From a distance, I surmised that editors – if they were actually editing work – were whittling authors’ works down to within an inch of their lives. I remember, for example, being left quite cold by the stoic quality of many of the stories in Philip Ó Ceallaigh’s 2010 Stinging Fly anthology, Sharps Sticks, Driven Nails.

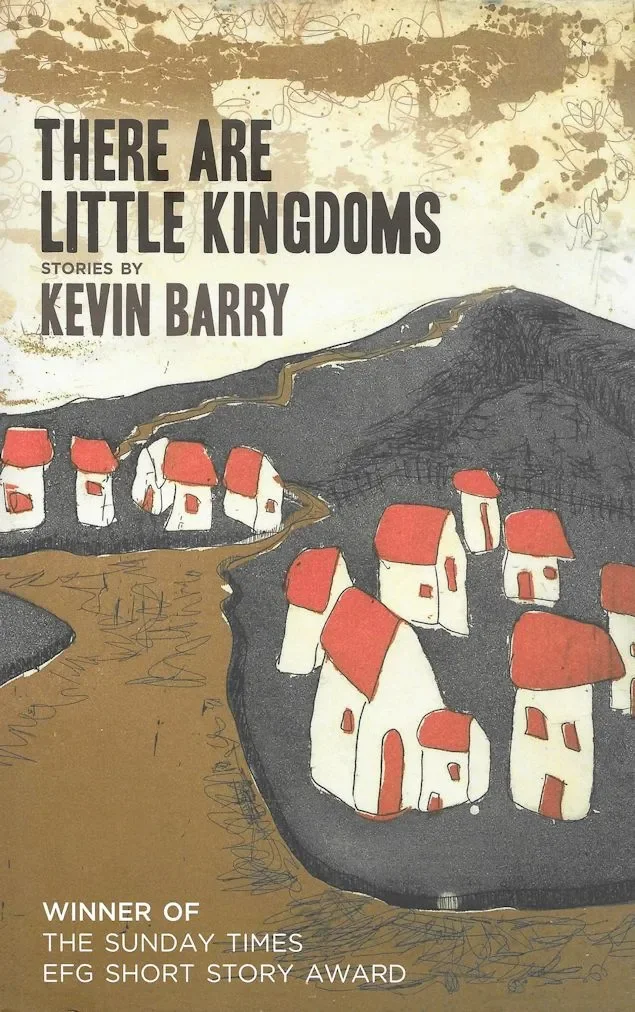

Of course, there were notable exceptions to these Quiet Solemn Stories. There’s that lovely quotation about how so many Russian writers emerged from beneath “Gogol’s Overcoat”; I think similarly that a whole grid of new Irish writers were suddenly electrified by reading Kevin Barry’s 2007 collection, There Are Little Kingdoms. To my ear, you can hear the Kevin Barry sound (the pleasure in language and dialogue; the appreciation for the absurd borne of the local) resonating in debut publications such as Colin Barrett’s Young Skins (2013); Lisa McInerney’s Glorious Heresies (2015); Danny Denton’s The Earlie King and The Kid In Yellow (2018); Nicole Flattery’s Show Them A Good Time (2019); and John Patrick McHugh’s Pure Gold (2021). In the same way that by 2023 I would detect the influence of Nicole Flattery and Sally Rooney’s work in the submissions to The Stinging Fly.

I began working with the Stinging Fly in February 2011, eight hours a week, as an editorial assistant, logging submissions and proofing the stories published in the magazine. In early 2012, I worked on Mary Costello’s The China Factory, providing editorial notes. At night, I would go home and tinker with my own short stories and a novel, becoming increasingly frustrated with the limits of this Quiet Solemness that I was unconsciously reproducing in my own work. To get to grips with what I was doing, I eventually went to the University of East Anglia in September 2012, and undertook the masters in Creative Writing, where the concentrated period of writing finally loosened the dam: I worked out how to reach a different pitch in my writing, to allow a different set of influences into my work, and I wrote most of the stories that became my first book. In the meantime, through the course’s weekly fiction workshops and through exchanging work with friends, I came to understand how feedback can close down a writer, or open things up entirely.

In autumn 2013, I returned to Dublin and was appointed Editor of The Stinging Fly. Very early on, reading the submissions, it become apparent to me that emerging authors, myself included, needed to be pushed to go beyond where they thought they were meant to stop – be that on the sentence level or in the construction of a scene. Mary Morrissy, for example, says that the emerging writer when writing a story is often “afraid to make a scene” – in both meanings of the word. In the 800-1000 stories I read each year in the submissions, I regularly encountered that resistance in the work I read: authors who were afraid to make “anything happen”, for fear that they were doing something as lowly or cheap as writing a plot. Starting out, it can seem safer for the writer, I think, to deal with inaction and inertia – to avoid genuine encounter. This is a tension that many emerging writers contend when they begin to write, and the experience is often mirrored in the work itself. Counter to this stream, I also read a lot of work where something suddenly brutal or murderous happened to an animal: an author hoping to shock an arrested story into life. In the call out for submissions to my first issue of the Stinging Fly, I wrote a manifesto which touches on some of these ideas, and captures the spirit of what I felt I was pushing towards at the time. The following year, I also wrote a list of 53 Ways To Improve Your Short Story, as part of the book promotion shlock-grind. (Were I to write these pieces today, my focus would naturally be very different, less hectoring, I hope; more considered.)

During my editorship, I also took on board something that Sean O’Reilly (an important figure at the magazine, and the Stinging Fly fiction workshop leader) often alluded to: how word-limits for journals and story competitions stifled so many story writers. At the Stinging Fly, we didn’t have a word-limit for submissions, but people would often submit work that they’d likely written with general word-limits in mind. So someone might send in a very neat and tidy, 2500 word story – which might be all and well and good, but which could become something far more interesting and complex if they allowed themselves to sink into the material and write beyond.

I had direct experience of this. During my masters, I wrote a story called “Castle View”, which began as an exercise in imitation. The first paragraph was a direct cover version of Joy Williams’s short story, “The Lover”, whose declarative opening sentences mesmerised me. In wanting to get closer to the story’s mysterious flow, I read and re-read it, and began to type out its opening sentences, changing a word here and there. Before I knew it, I had a second paragraph of all my own, and very quickly, I had 2500 words of an entirely new story. I thought the story was complete because this was the length that so many magazines and competition asked for. I remember sitting on my bedroom floor in Norwich, believing the story was good, but intuiting that there was further ground to break. I couldn’t decide whether to stick or twist, fearing that if I took I broke it apart, I might end up wrecking the whole thing. Crucially, we were allowed to submit stories of up 5000 words to the workshop, so I took a deep breath and decided to go back in, expanding the story from the inside out. I thickened the weave, writing new vignettes between existing scenes, and really sunk into the story’s feeling, extending its duration by a couple hours. A week later, the story had reached 5700 words. I printed it at the college library and took out my red pen. Sat there in the library stall, reading the story’s final paragraph, a chill passed through me, and I felt for the first time in my life that I was a real writer. The story had achieved a density and depth I’d never before gotten down on paper. It was as if the story had become the thing it had always meant to be, and it felt truer for my not having gotten in its way.

‘Whittlling up’ is how Grace Paley, in an interview, once described this process. In my work as an editor, and later as a mentor at The Stinging Fly, ‘whittling up’ was something I encouraged authors to do, as I worked with them through multiple drafts. I’d ask an author to push through – and move towards the heat. There’s something here, I’d say, pointing towards a description, a word choice, or a particular passage. Go towards it, see what’s there. You can always draw back afterwards. The aim wasn’t so much to get authors to write longer stories, per se, but to give the permission to fully explore the material that arose in their work – to sink into it – and unearth the story’s buried intentions.

Over the course of several drafts, and many conversations – sometimes over many months – I urged authors to re-form their work, to find new entry points, all in the service of helping them listen to what the story wanted to say. Julio Cortázar once compared the writing of a story to pulling out of himself “some kind of creepy creature” – and this pulling out of one’s self is how I sometimes envisioned writing: the string of sentences a knotted rope that only emerged as the writer wrote out, expressing through the movements of the story the things they ordinarily could not express. Along the way, an author might well get lost or lose hope; and I felt it was my role to say, It’s okay, this is the work, keep going – a companion in the dark. If an editor only gets one chance to edit a piece, they can certainly improve what’s there by solely making cuts. But if an editor has time on their side, and they’re able to build trust with an author, they can urge them to take their work to a different realm entirely.

With some authors, my suggestions might be purely formal: I’d suggest a change in the story’s point of view, or propose a closer third person narration; or a more condensed timeline; or recommend recasting the story in the past tense, or beginning the story at a later, or earlier, point. Tip the story upside down and and give it a shake, I’d say. See what loose change falls out of its pockets. Sometimes, I’d prescribe a story or film that might chime with or illuminate what the author was reaching for. Sometimes, where I sensed strange or subversive currents flowing beneath the work, I encouraged the author to follow their instinct and move beyond whatever invented rules were holding them back from letting loose. On a couple of occasions, I asked an author to whittle up what was originally a one-paragraph conceit into a 4000-word story, that went past what both the author I thought a short story was ever meant to be. If an author were stalled, I sometimes suggested a change in their writing practise, encouraging them to write fiction from a different mental place altogether. (In 2021, I developed this idea further, asking four authors to write a story in a single night.) Sometimes I told authors to forget the word ‘story’ entirely, and to just to go where the language was leading them, even if the path was unclear. Underpinning all this was a strong conviction that when an artist moves beyond the edges of what they think they know, they will always discover something new.

—2025